While many people argue that home economics classes are outdated (and patriarchal), the whole point of them was to equip young people with the practical skills they needed to live life as independent adults.

Historically, the purpose of these courses was to professionalize housework, to provide intellectual fulfillment for women, and to emphasize the value of “women’s work” in society and to prepare them for the traditional roles of sexes.

By definition, home economics is “the art and science of home management,” meaning that the discipline incorporates both creative and technical aspects into its teachings.

Since the nineteenth century, schools have been incorporating home economics courses into their education programs. In the United States, the teaching of home economics courses in higher education greatly increased with the Morrill Act of 1862.

Signed by Abraham Lincoln, the Act granted land to each state or territory in America for higher educational programs in vocational arts, specifically mechanical arts, agriculture, and home economics.

Such land grants allowed for people of a wider array of social classes to receive better education in important trade skills.

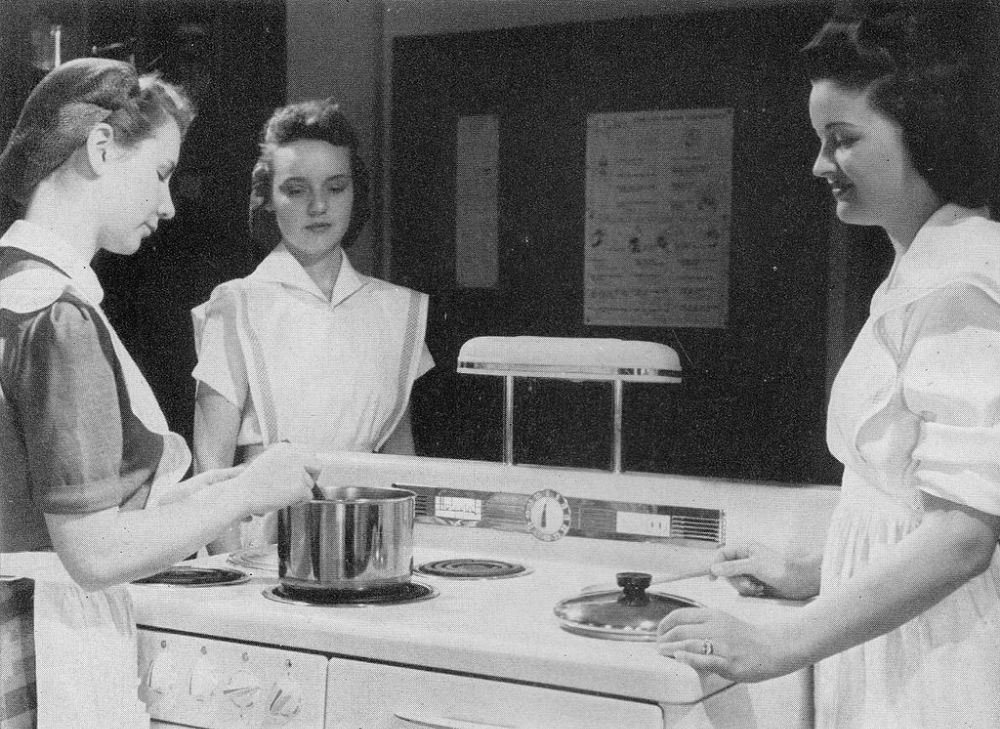

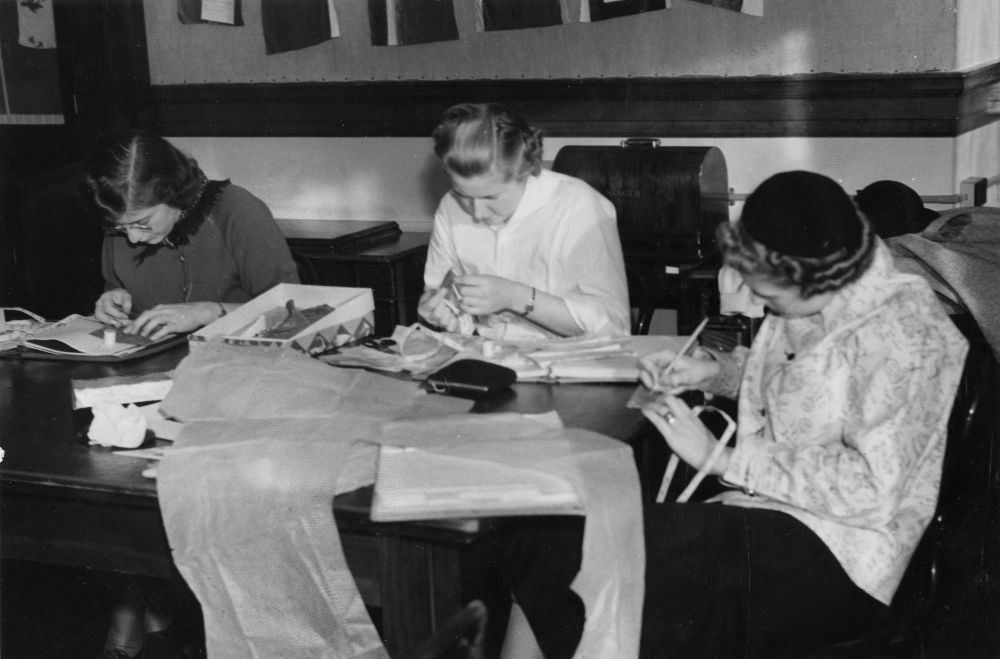

Home economics courses mainly taught students how to cook, sew, garden, and take care of children. The vast majority of these programs were dominated by women.

Home economics courses mainly taught students how to cook, sew, garden, and take care of children. The vast majority of these programs were dominated by women.

Home economics allowed for women to receive a better education while also preparing them for a life of settling down, doing the chores, and taking care of the children while their husbands became the breadwinners.

Home economics in the United States education system increased in popularity in the early twentieth century. It emerged as a movement to train women to be more efficient household managers.

At the same moment, American families began to consume many more goods and services than they produced.

To guide women in this transition, professional home economics had two major goals: to teach women to assume their new roles as modern consumers and to communicate homemakers’ needs to manufacturers and political leaders.

From 1900 to 1917, more than thirty bills discussed in Congress dealt with issues of American vocational education and, by association, home economics.

From 1900 to 1917, more than thirty bills discussed in Congress dealt with issues of American vocational education and, by association, home economics.

Americans wanted more opportunities for their young people to learn vocational skills and to learn valuable home and life skills.

However, home economics was still dominated by women and women had little access to other vocational trainings.

As stated by the National Education Association (NEA) on the distribution of males and females in vocations, “one-third of our menfolk are in agriculture, and one-third in non-agricultural productive areas; while two-thirds of our women are in the vocation of homemaking”.

Practice homes were added to American universities in the early 1900s in order to model a living situation, although the all-women ‘team’ model used for students was different from prevailing expectations of housewives.

Practice homes were added to American universities in the early 1900s in order to model a living situation, although the all-women ‘team’ model used for students was different from prevailing expectations of housewives.

For example, women were graded on collaboration, while households at the time assumed that women would be working independently. Nevertheless, the practice homes were valued.

These practicum courses took place in a variety of environments including single-family homes, apartments, and student dorm-style blocks.

For a duration of a number of weeks, students lived together while taking on different roles and responsibilities, such as cooking, cleaning, interior decoration, hosting, and budgeting. Some classes also involved caring for young infants, temporarily adopted from orphanages.

There was a great need across the United States to continue improving the vocational and homemaking education systems because demand for work was apparent after World War I and II.

There was a great need across the United States to continue improving the vocational and homemaking education systems because demand for work was apparent after World War I and II.

Therefore, in 1914 and 1917, women’s groups, political parties, and labor coalitions worked together in order to pass the Smith-Lever Act and the Smith-Hughes Act.

The Smith-Lever Act of 1914 and the Smith-Hughes Act of 1917 created federal funds for “vocational education agriculture, trades and industry, and homemaking” and created the Office of Home Economics.

Throughout the 1940s, Iowa State College (later University) was the only program granting a master of science in household equipment.

However, this program was centered on the ideals that women should acquire practical skills and a scientifically based understanding of how technology in the household works.

For example, women were required to disassemble and then reassemble kitchen machinery so they could understand basic operations and understand how to repair the equipment.

In doing so, Iowa State effectively created culturally acceptable forms of physics and engineering for women in an era when these pursuits were not generally accessible to them.

Throughout the latter part of the twentieth century, home economics courses became more inclusive. In 1963, Congress passed the Vocational Education Act, which granted even more funds to vocational education job training.

Throughout the latter part of the twentieth century, home economics courses became more inclusive. In 1963, Congress passed the Vocational Education Act, which granted even more funds to vocational education job training.

Home economics courses started being taught across the nation to both boys and girls by way of the rise of second-wave feminism. This movement pushed for gender equality, leading to equality of education.

In 1970, the course became required for both men and women. Starting in 1994, home economics courses in the United States began being referred to as “family and consumer sciences” in order to make the class appear more inclusive.

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s

Home economics class, 1920s-1930s