A group of Navajo in the Canyon de Chelly, Arizona. 1904.

Born in Wisconsin in 1868, Edward Sheriff Curtis took to photography at an early age. In 1895 he photographed Princess Angeline, the daughter of the Duwamish Chief Seattle, for whom the city was named.

That encounter sparked Curtis’ lifelong fascination with the cultures and lives of Native American tribes. He soon joined expeditions to visit tribes in Alaska and Montana.

In 1906, Curtis was approached by wealthy financier J.P. Morgan, who was interested in funding a documentary project on the indigenous people of the continent. They conceived a 20-volume series, called The North American Indian.

With a trail wagon and assistants traveling ahead to arrange visits, Edward Curtis set out on a journey that would see him photograph the most important Native Americans of the time, including Geronimo, Red Cloud, Medicine Crow, and Chief Joseph.

The trips were not without peril—impassable roads, disease, and mechanical failures; Arctic gales and the stifling heat of the Mohave Desert; encounters with suspicious and “unfriendly warriors.”

But Curtis managed to endear himself to the people with whom he stayed. He worked under the premise, he later said, of “We, not you. In other words, I worked with them, not at them.”

Sioux chiefs. 1905.

On wax cylinders, his crew collected more than 10,000 recordings of songs, music, and speech in more than 80 tribes, most with their own language.

To the amusement of tribal elders, and sometimes for a fee, Curtis was given permission to organize reenactments of battles and traditional ceremonies among the Indians, and he documented them with his hulking 14-inch-by-17-inch view camera, which produced glass-plate negatives that yielded the crisp, detailed and gorgeous gold-tone prints he was noted for. The Native Americans came to trust him and ultimately named him “Shadow Catcher,”.

In his efforts to capture and record what he saw as a vanishing way of life, Curtis sometimes meddled with the documentary authenticity of his images.

He posed his subjects in romanticized settings stripped of signs of Western civilization, more representative of an imagined pre-Columbian existence than the subjects’ actual lives in the present.

“Noble savage” stereotypes aside, Curtis’ vast body of work is one of the most impressive historical records of Native American life at the beginning of the 20th century.

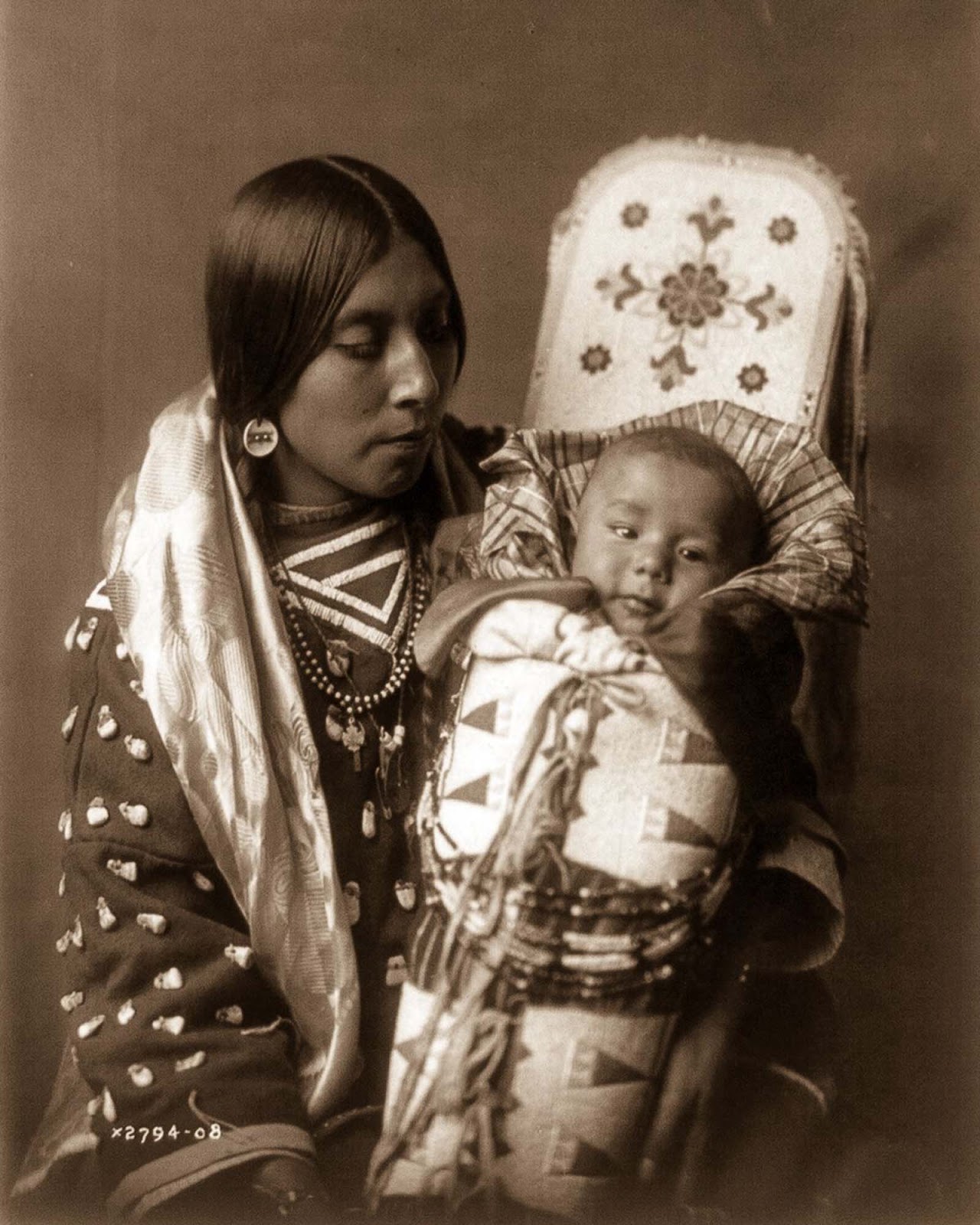

An Apsaroke mother and child. 1908.

Luzi, of the Papago tribe. 1907.

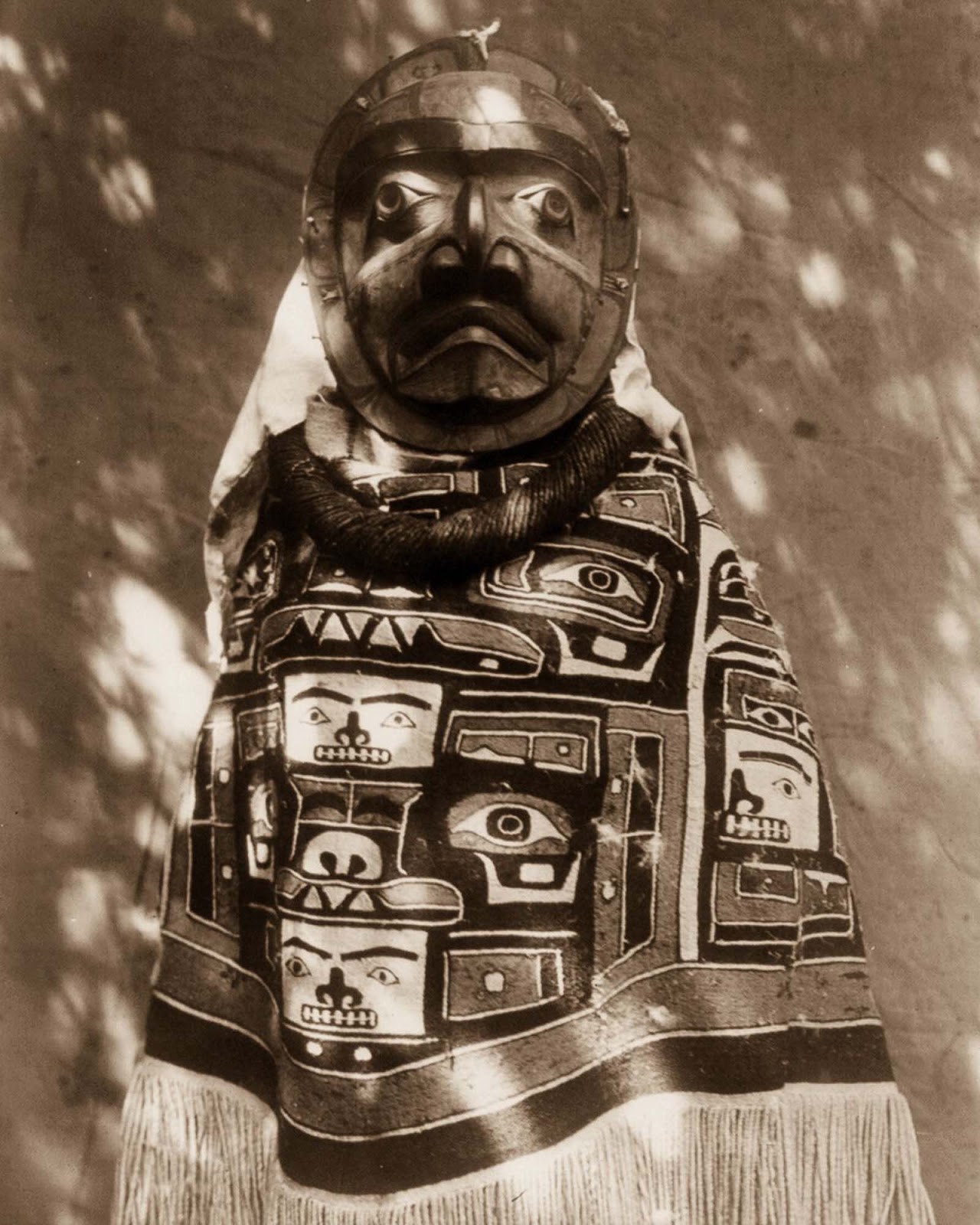

A Qagyuhl woman wears a fringed Chilkat blanket and a mask representing a deceased relative who had been a shaman. 1914.

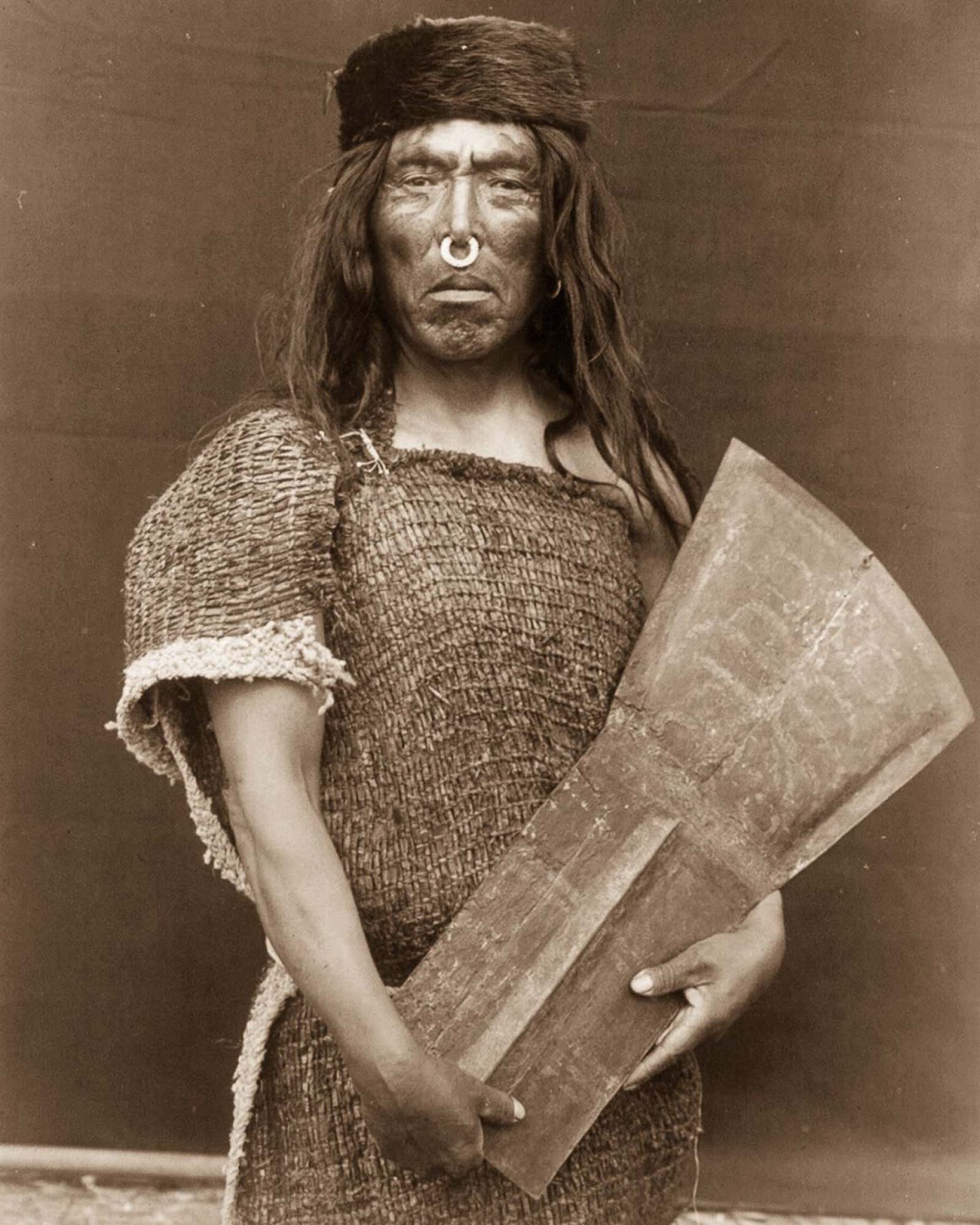

Hakalahl, a Nakoaktok chief. 1914.

A Kwakiutl gatherer hunts abalones in Washington. 1910.

Piegan girls gather goldenrod. 1910.

A Qahatika girl. 1907.

A young member of the Apache tribe. 1910.

Eskadi, of the Apache tribe. 1903.

Kwakiutl people in canoes in British Columbia. 1914.

Kwakiutl people in canoes in British Columbia. 1914.

A Kwakiutl wedding party arrives in canoes. 1914.

A Koskimo man dressed as Hami (“dangerous thing”) during a Numhlim ceremony. 1914.

A Qagyuhl dancer dressed as Paqusilahl (“man of the ground embodiment”). 1914.

A Qagyuhl man dressed as a bear.

Qagyuhl dancers. 1914.

Nakoaktok dancers wear Hamatsa masks in a ritual. 1914.

Hollow Horn Bear, a Brulé man. 1907.

A Tewa girl. 1906.

An Apache woman reaps grain. 1910.

A Hidatsa man with a captured eagle. 1908.

Piegan tepees. 1910.

A Sioux hunter. 1905.

A Kwakiutl shaman. 1914.

A Kwakiutl man wearing a mask depicting a man transforming into a loon. 1914.

An Apsaroke man on horseback. 1908.

A Klamath chief stands on a hill above Crater Lake, Oregon. 1923.

Iron Breast, a Piegan man. 1900.

Black Eagle, an Assiniboin man. 1908.

Nayenezgani, a Navajo man. 1904.

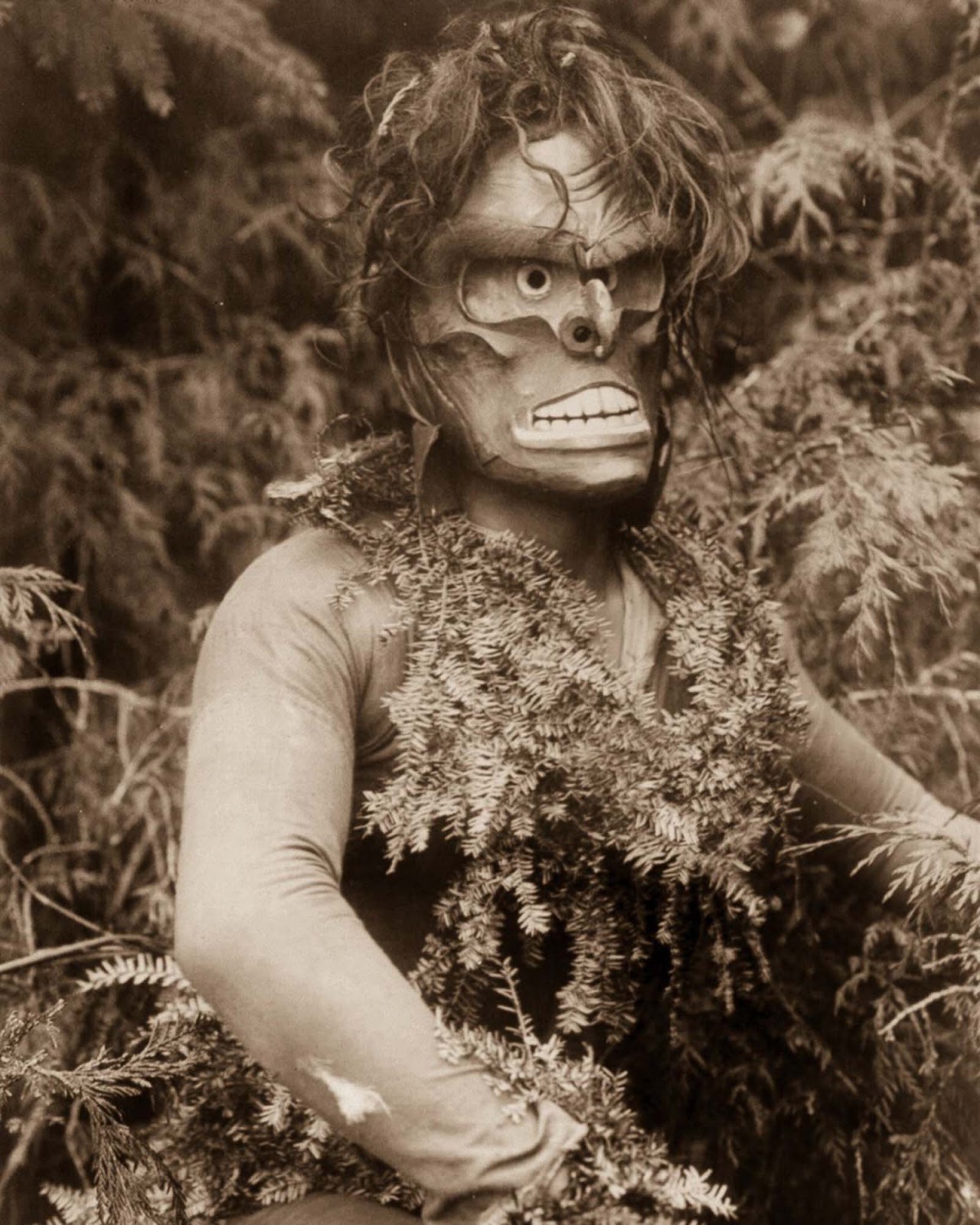

A Kwakiutl person dressed as a forest spirit, Nuhlimkilaka, (“bringer of confusion”). 1914.

A Hupa woman. 1923.

Mowakiu, a Tsawatenok man. 1914.

Piegan chiefs. 1900.

Vash Gon, a Jicarrilla man. 1910.

“The Hopi Maiden.” 1905.

A Jicarrilla girl. 1910.

A Zuni woman. 1903.

Iahla, also known as “Willow,” of the Taos Pueblo. 1905.

A Papago woman. 1907.

A Maricopa woman. 1907.

Okuwa-Tsire, also known as “Cloud Bird,” of the San Ildefonso Pueblo. 1905.

A Maricopa woman with arrow-brush stalks. 1907.

A Cahuilla woman. 1924.

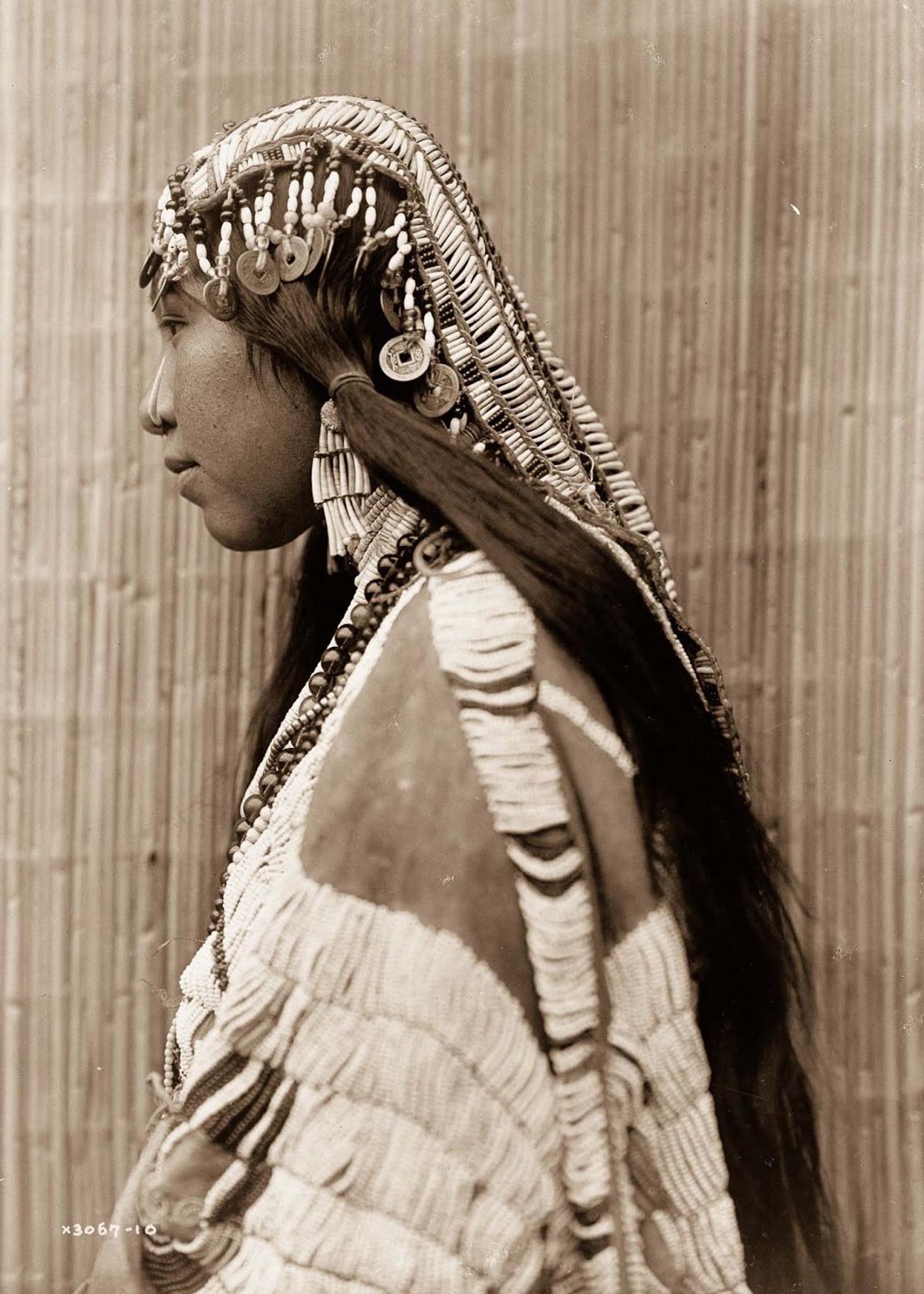

A Kwakiutl chief’s daughter. 1910.

A Kutenai duck hunter. 1910.

Medicine Crow, of the Apsaroke tribe. 1908.

A Wishran girl. 1910.

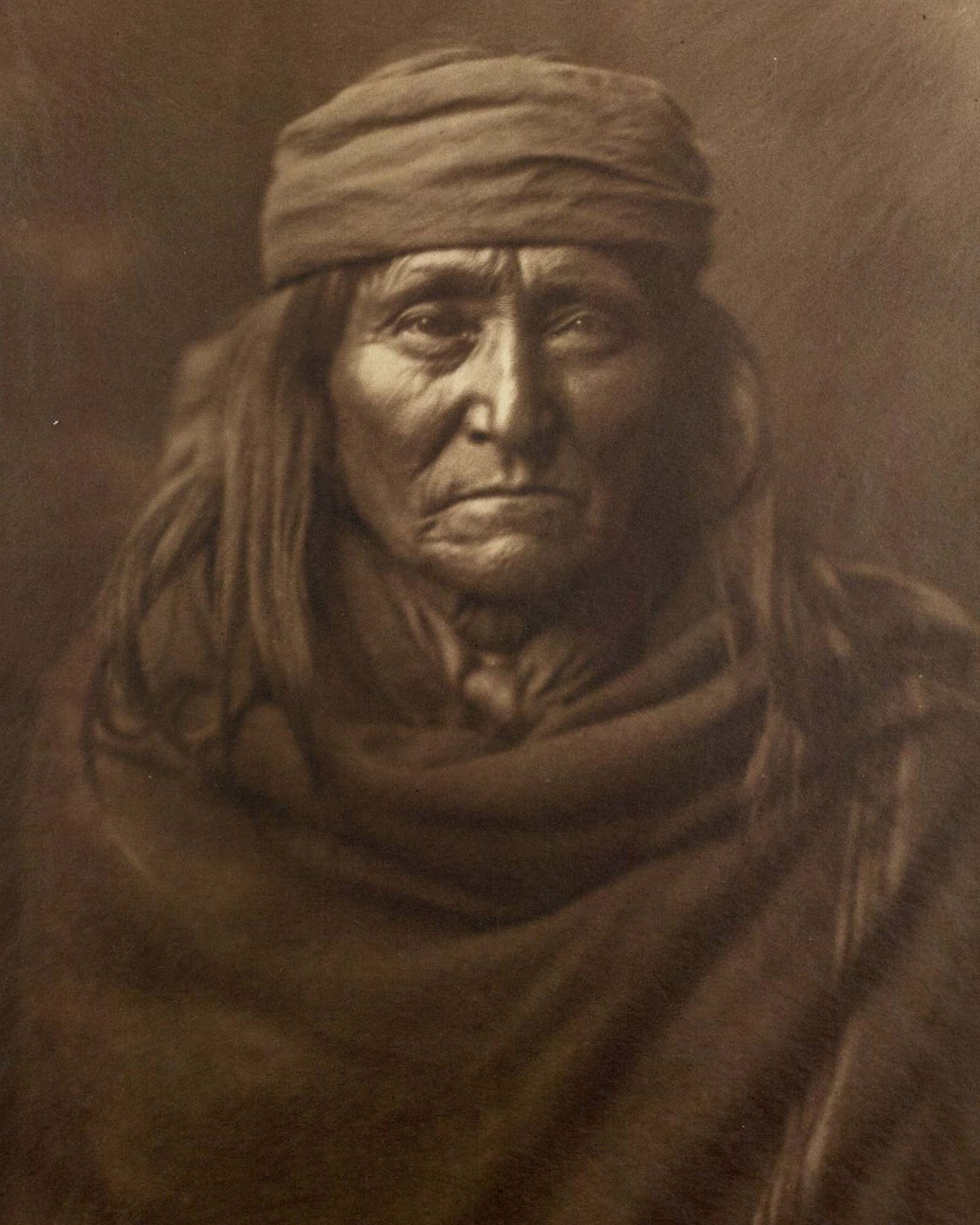

Nesjaja Hatali, Navajo medicine man. 1904.

Members of the Qagyuhl tribe dance to restore an eclipsed moon. 1910.